Conciliarism

By Orlando Fedeli - Conciliarism, or Conciliar Movement, was repeatedly condemned by the church. In our times it appears again behind of some sedevacantists ideas

Conciliarism is the theological error that claims that the Ecumenical Council is superior to the Pope, being able to judge, condemn and even depose him.

The first roots of the conciliarist error — which extends its branches to the present day in sedevacantism — were born during the Great Schism of the West (from 1378 to 1417).

After the return of the Popes from the Captivity of Avignon, Urban VI was elected Pope in Rome. The Conclave was dramatic, because the people of Rome demanded that a Roman Cardinal be elected pope. And Urban VI was Italian, but not Roman.

After nine months of government, some Cardinals led by Cardinal Pedro de Luna, rebelled against Urban VI, alleging lack of freedom in the Conclave that had elected him, and, gathered in a false and illegitimate Conclave, electing an anti-Pope — Cardinal Robert of Geneva —, who took the name of Clement VII (1378-1394). Thus began the Western Schism, which had several anti popes established with their courts in Avignon, France.

Even during the Middle Ages, in the wake of the heretical movement of Spirituals Franciscan (Fraticelli) and the revolt of Emperor Louis of Bavaria against Pope John XXII, the heretic Marsilio of Padua, author of Defensor Pacis, supported the thesis of the illegitimacy of Pope John XXII, as well as as the necessity and legitimacy of deposing him.

Later, Henry of Langenstein expressly defended the thesis that the Council was superior to the Pope, and that it had the power to judge and depose a pontiff, convoke a new conclave and elect a new Pope.

During the Great Western Schism, Emperor Sigismund III forced the anti-Pope John XXII to convoke a Council in Constance (1414) as a continuation of the Council of Pisa.

This Council of Constance (1414-1417) aimed to restore the unity of the Church compromised by the Great Schism, to reform the Clergy, and to root out the heresies of that time.

The unity of the papacy was achieved with the election of Cardinal Colonna, who took the name of Martin V (1417-1431). This Pope condemned the conciliarist error, defended by the Council of Constance, and dissolved that Council.

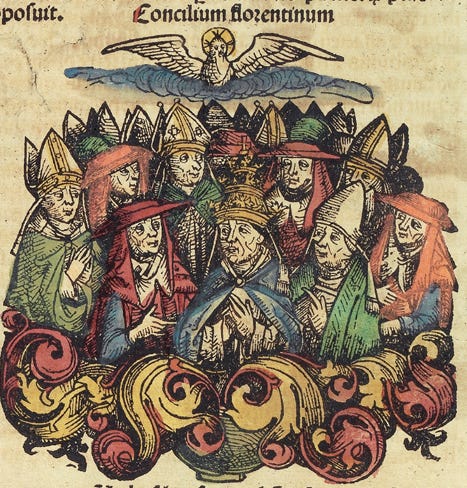

Afterwards, Pope Eugene IV (1431-1447) convened the Council of Basel to conclude what the Council of Constance had not concluded. Having started on December 14, 1431, the Council of Basel soon demonstrated conciliarist tendencies which caused the Pope to dissolve it four days after it started. Reopened by the same Pope Eugene IV, and because the council had rebelled against the Pope and defended the superiority of the Council over the Pope, it was dissolved. A true and legitimate Council was transferred to Ferrara, and then to Florence.

On May 16, 1439, the Council of Basel approved the heretical thesis of Conciliarism, when it promulgated the following canon:

The Holy Council of Basel declares and defines the following:

1. It is a truth of the Catholic faith that the General Council, representing the Universal Church, has an authority superior to that of the Pope and (superior) to any other people;

2 It is a truth of the Catholic faith that the Pope cannot in any way dissolve, transfer or extend the General Council representing the universal Church, unless the Council consents to it

3. Anyone who contradicts the present truths must be regarded as a heretic.Council of Basel, apud Rhorbacher, Histoire de l'Église, Gaume et Frères, Paris 1866, vol. XI, p. 324

This was the formulation of the conciliarist heresy.

Decisions of the Council of Basel were also the basis for the King of France, Charles VII, to promulgate the so-called Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges (1438), the foundation of the future Gallican church.

Pope Eugene IV, in 1439, at the Council of Florence, condemned the “conventículo” of Basel and anathematized the conciliarist errors expressed both at the Council of Constance and at Basel.

The Council of Basel resisted the decisions of Pope Eugene IV, rebelled and held a meeting decreeing that the Pope had no power to dissolve the Council. Members of the Council of Basel condemned and then deposed Pope Eugene IV, electing Cardinal Amadeus, Duke of Savoy, as the anti-Pope Amadeus VIII (1439-1449).

Finally, in 1449, the anti-pope Amadeus VIII renounced his illegitimate title, submitting to the reigning Pope Nicholas V. The Council of Basel, then in Lausanne, completely demoralized, dissolved, accepting the reigning Pope. It was the complete defeat of the conciliarist thesis.

Pope Pius II solemnly condemned conciliarism through the Bull Exsecrabilis (January 10, 1459, or 1460 in the current calendar). Here is the central text of this bull:

The execrable and hitherto unheard of abuse has grown up in our day, that certain persons, imbued with the spirit of rebellion, and not from a desire to secure a better judgment, but to escape the punishment of some offense which they have committed, presume to appeal to a future council from the Roman Pontiff, the vicar of Jesus Christ, to whom in the person of the blessed PETER was said: "Feed my sheep" (Jn 21,17), and, "Whatever thou shalt bind on earth, shall be bound in heaven" (Mt 16,19). . . . Wishing therefore to expel this pestiferous poison far from the Church of Christ and to care for the salvation of the flock entrusted to us, and to remove every cause of offense from the fold of our Savior . . . we condemn all such appeals and disprove them as erroneous and detestable.

Pius II, Bull Execrabilis, Denzinger, 717

Also Pope Leo X reaffirmed the right of supremacy of the Popes over the Councils in the Bull Pastor Aeternus of 1516, in which he also condemns the Pragmatic Sanction:

Nor should this move us, that the sanction [pragmatic] itself, and the things contained in it were proclaimed in the Council of Basle … since all these acts were made after the translation of that same Council of Basle from the place of the assembly at Basle, and therefore could have no weight, since it is clearly established that the Roman Pontiff alone, possessing as it were authority over all Councils, has full right and power Of proclaiming Councils, or transferring and dissolving them, not only according to the testimony of Sacred Scripture, from the words of the holy Fathers and even of other Roman Pontiffs, of our predecessors, and from the decrees of the holy canons, but also from the particular acknowledgment of these same Councils.

Leo X, Bull Pastor Aeternus, of December 19, 1516, Denzinger, 740

Now, if the Pope has full power over Councils, if no Council can judge, condemn or depose a Pope, no organ of the Church, no group, no individual, no group of Cardinals or Bishops, however numerous, has the power or right to declare a Pope as being deposed, or to declare that he has lost Pontifical power. No one can declare the see as vacant by human judgment. No one can depose a Pope. Therefore, it is in the Code of Canon Law that the Pope can be judged by no one.

Only after his death can a Pope be judged by another Pope. In life, never.

And with that, once again, the delusional and anarchistic thesis of sedevacantism is destroyed.

São Paulo, November 24, 2008.

Orlando Fedeli